“Take your time.” That’s what I tell myself when things start to get a little out of hand at the store.

At the beginning of a week-long class, I warn students that this is an artificial way to work. Besides the stress of navigating an unfamiliar workshop and practicing unfamiliar techniques, there is the issue of time. For starters, most of us are not used to working with wood for 8-10 hours a day. In addition, allocating an arbitrary number of days to complete a project is often unrealistic. The idea of deadlines we set for ourselves can also affect the experience of working in our own workshops.

Yes, we often have expectations about what we want to accomplish in an hour or an afternoon at the store. Sometimes we achieve the goal, and sometimes we fail. The danger lies in trying to speed up the process to fit the time we have. One big lesson I’ve learned is that trying to speed up rarely gets anything done faster. The advice I give students is that it will take a long time. We all have an optimal speed to work with, and trying to speed up a process is never going to work. I know that’s easier said than done in the organized chaos of a typical classroom.

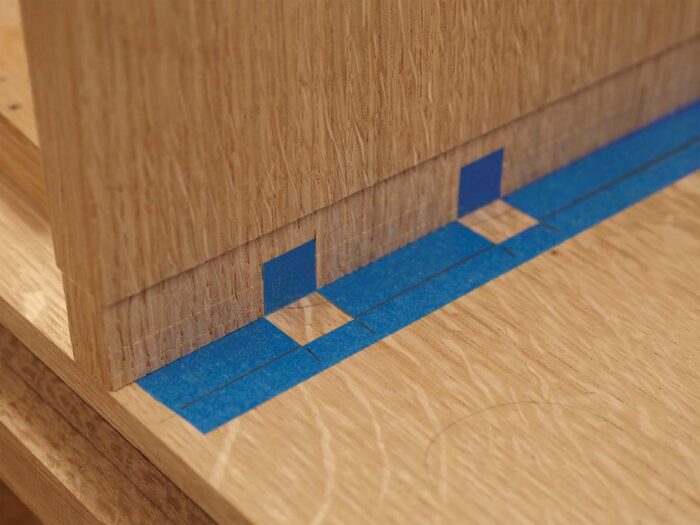

When I’m back in my shop, when I find myself in a rush, when I’m trying to figure out which task is the next most important—the one that will get me to the finish line the fastest—I try to take a break. When I’m working on a home project, I tend to work at a fast pace. That pace leads to a process and workflow that produces a level of work that I’m generally satisfied with, but often falls short of what I consider “perfect.” On other occasions—working on a commissioned piece, for example, where “perfection” is the goal—I find that it’s not just a matter of trying harder but often involves rethinking the way I work. Something as simple as the way I use my marking gauge can make a difference. While holding the board in one hand and engraving with the other generally produces accurate results, holding the board in place, while more laborious and time-consuming, provides an added level of control. As a result, I’ve spent a much larger portion of my afternoon in the workshop recently putting in holes and joints than I normally would. Even though it added more pinning and unpinning to my routine, I didn’t really mind it. In fact, I enjoyed the time more than I would have if I had been rushing around all day. I was more in control of the process, and I was confident in the results when I was done.

While we tend to focus on the quality of the final product while we work, focusing on the quality of the time we spend in the shop can bring us closer to that piece we were hoping to create.

Editor’s Message: Technology and the Future of Woodworking

Mike Pekovich answers the question: What will woodworking look like 50 years from now?

Editor’s Message: Get Started in Woodworking

Don’t let the desire to build something “important” keep you from building anything at all.

Editor’s Message: Knowing What’s Important (and What’s Not)

Think about what’s most important and your building will become more efficient and enjoyable.

Sign up for our e-newsletter today and get the latest techniques and how-tos from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.