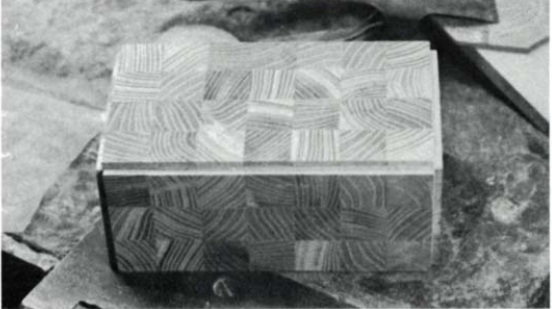

When a branch of a tree is cut crosswise into thin slices and then laid over the surface of a box or piece of furniture, the grain and shape of the slices resembles an oyster shell. Hence the name for this traditional decoration technique: oyster shell. Ernest Joyce mentions this method in his excellent book, The Encyclopedia of Furniture Making, and it, along with a photo of a beautifully covered cigarette box, prompted me to try my luck at oyster shelling a small plywood box. An unproductive plum tree provided me with close-grained wood, a deep red heartwood and a creamy gumwood—the most attractive for this purpose. A carob branch, ochre-colored in the middle, helped me discover more tricks of the trade.

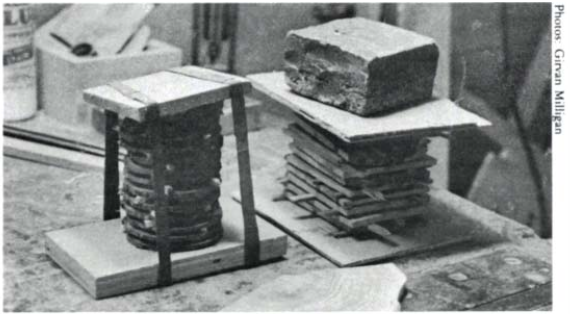

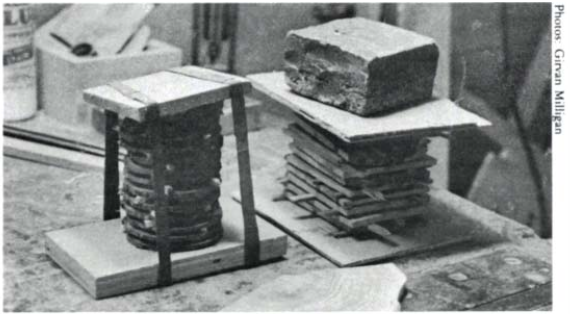

Cutting round sections with a bandsaw is easier and safer if you put a clamp on the branch or trunk to prevent rolling. You can cut smaller branches with a table saw or radial arm saw. Cutting diagonally rather than straight across results in ovals, which look more like clamshells. The angle of the cut also changes the grain pattern, though it also creates a grain direction issue, which must be taken into account in the final surface finish. I hand cut my slices to 1/8-inch thickness and stack them with narrow spacings between them. Joyce suggests putting a weight on the stack, which works fairly well until one of them accidentally falls out. Tying the stack with strips of inner tube keeps the slices flat and allows the stack to be easily moved from one location to another.

Because they are thin, the strips dry quickly. I have experimented with burying the strips in dry sand, placing several thick layers of newspaper between them in the stacks, and securing them with plugs without using spacers or paper. The sand was the least effective because it provided no pressure and allowed the pieces to bend and deform badly. However, short lengths of branches can be buried in sand with better results. Coating the ends of the branches with glue also helps reduce deformation. I placed one of the stacks over an oil burner to speed up the drying time—a lesson in patience. The glued stacks that dried slowly in my cold shop produced more deformation-free strips, although even those that were smoothed by other methods produced more usable material.

When the oysters are dry, you can cut them into squares, rectangles, polygons, or fit them together in the more natural curves of circular sections. In all cases, the joints should be precise. Straight edges are obviously easier to fit and keep square; I use a copy board and a ruler. Check the fit of the joint by holding the pieces up to a bright light. High points can be cut off and checked again. When working with curved joints, you can sometimes chase the high points from one end of the curve to the other because removing wood from one point changes the relationship between the other parts of the curve. Whatever the shape of the pieces, keep in mind the size and shape of the surface to be covered so that the final product has a balanced pattern. You can match adjacent strips of branch to start a pattern in the middle and balance them with other matching pieces toward the edges.

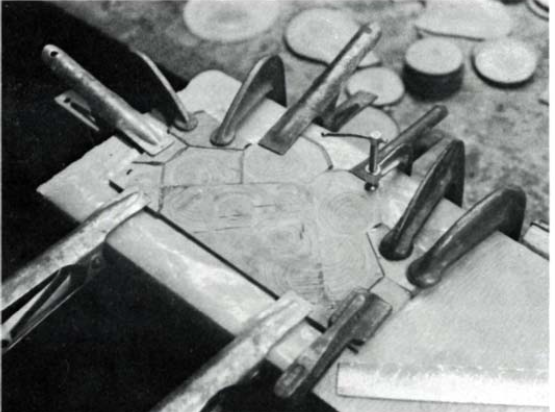

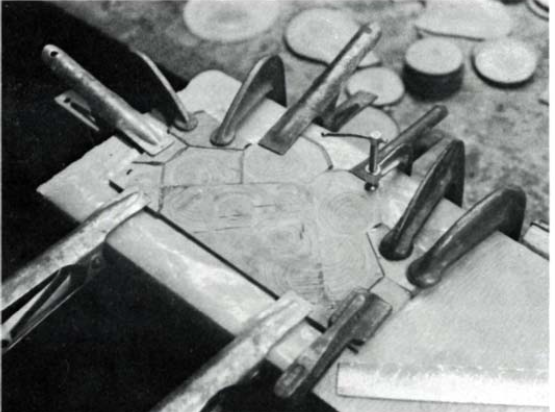

When you get the right fit, glue the pieces together one or two at a time. If the pieces are square, you can glue a whole row at a time. You can lay out a whole jigsaw puzzle and glue them all together, but the joints will probably be tighter and it will be less nerve-wracking to do it gradually. Experiments with adhesives including white glue, solder glue, yellow glue, and epoxy have shown favor for the five-minute epoxy. You can mix it in small enough quantities for each joint and its strength and quick setting allow the work to move quickly. A board covered with a piece of polyethylene and held in pliers is a good surface for assembly. The polyethylene releases any glue and eliminates the need to scrape the paper. Small clips hold the pieces in place while the glue sets, preventing them from bending. Tape all the edges, not just the joint: clams tend to bend if they are not held flat. When you have assembled an area large enough to cover the surface to be veneered, cut the assembly slightly larger and secure it between supports or weight it down to the surface. Smooth out any high spots.

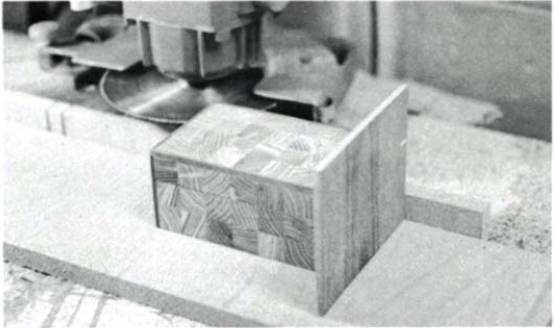

Now build a box to receive the collected oyster shells. Plywood provides a more stable base than solid wood, with birch plywood being the easiest to work with. A 3/8-inch thick plywood box, with another 3/32-inch or so of boards added, doesn’t look clumsy and has enough room to install hinges. My joinery is simple. I line up the front and back of the box and fix the sides, all glued and nailed. I screw the top and bottom together, glued and nailed. Since the veneer will cover the entire exterior, the joinery is hidden; any strong, simple joint will do. There is no opening in the box yet; cutting the top is a later step.

Before gluing, coat the back of the boards with a thin layer of glue and let dry to increase the strength of the glue bond between the end grains. Cut each board so that it is flush with the edges of the box. When all the boards are glued and held in place and the glue has set, scrape the surface evenly, being careful to scrape toward the center to avoid chipping the edges. When two pieces cut at an angle are matched, you can better handle the sudden change in grain in the middle of the board by scraping across both. A heavy-duty saw blade with polished teeth and all square-sanded edges makes an excellent scraper. It is 12 inches long, flexible, and made of superior steel. Sanding square on a fine-grain wheel gives a consistent edge, and its length provides the equivalent of half a dozen ordinary scrapers. When the section used becomes dull, it only takes a few inches to slide the blade down to get a fresh new edge. There are four edges. The edge with the teeth remains slightly wavy after sanding, and this edge gives a rougher but faster cut. The old Victrola spring also gave me some excellent scraping yards. An 80 grit belt sander will quickly cut away the excess, but be careful not to burn the wood. In one experiment with yellow glue, the heat from the sander softened the glue. Too much heat can also cause scratches and warping.

When you’re done scraping, cut a ridge around the top and on all four corners to accommodate a strip of edge the thickness of the board. Cut the edge larger than necessary, then scrape it so that it is flush with the surface. A contrasting color, lighter or darker than the floor color, looks attractive. Narrow strips of inner tube wrapped around the box provide satisfying clamps to hold the edge in place.

The entire box can now be sanded to almost its final state. There is a bit more handling before it is finished, which can cause scratches, so it is best to leave the final sanding until last. Cut the box open on a radial arm saw in its horizontal position, using a fine-toothed blade, or on a table saw. Be sure to support the corners with a piece of scrap to reduce the chance of cracking the edges.

If you used plywood for the box, cover the box with either veneer or Formica. The matte white Formica provides a nice, light interior and is easy to keep clean. Line up the exposed edges of the plywood with the bottom of the box. I usually install four plugs made with a plug cutter on the bottom of the short legs, which prevents the bottom from getting scratched.

Finish sanding in good light, checking for any scratches you think might be there. They probably are. The final finish is largely a matter of preference, but it is important that the surface is completely sealed. Polyurethane is durable and with a number of coats and careful rubbing gives a beautiful finish. Watco oil also gives a nice finish, and allows for a much easier finish than polyurethane. However, Watco is not moisture resistant, and in one case finished with it there seemed to be more expansion and contraction of individual pieces.

Be prepared for wood movement. Sectional pieces are very sensitive to changes in humidity. Keep finished boxes away from direct sunlight and heating appliances. To minimize peeling and cracking, cut pieces as thin as possible, size them before placing them, and use a moisture-resistant finish. However, you may have to accept small cracks and glue lines that vary in size as part of the design.

A variation that is not true oyster work (because the wood has no core) can be made from all those little scraps you hesitate to throw away. Many woods have beautiful and interesting end grains, and careful matching and blending can result in a beautiful piece of work.

Sign up for our e-newsletter today and get the latest techniques and how-tos from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.